Creatures as stable spells

How should the effectiveness of creatures as a group be evaluated in MTG? What unique characteristics is it important to know about?

Creatures as a group are stable, almost certainly the most stable in a limited environment, except perhaps for removals (which themselves are stable because creatures are abundant). The explanation for this is the many roles that creatures are able to play in the game: 1. they mainly carry the burden of victory by eating away at the opponent’s life points; 2. they are able to block the opponent’s creatures and thus protect the player’s life points; 3. often, they benefit from abilities that give players a certain advantage―causing damage to creatures (Prodigal Pyromancer), empowering other creatures (Ghost Warden), gaining life (Alabaster Host Sanctifier) and more. This flexibility characteristic of creatures as a group makes them very desirable in a limited environment: most of the spells we normally include in the deck are creatures. A deck that does not include a sufficient number of creatures will be of poor quality, regardless of the nature of the other spells it includes. However, to say that creatures are stable as a group does not mean that all creatures are stable. Certain creatures, for example, are very expensive in terms of mana and are therefore defined as situational.

Prodigal Pyromancer

mana costs:

mana amount: 3

complexity: 2

Ghost Warden

mana costs:

mana amount: 2

complexity: 1

Alabaster Host Sanctifier

mana costs:

mana amount: 2

complexity: 1

In the spring of 2001, I made it to a draft tournament for the very first time in my life. Being a month-old Magic player, I was quite anxious. Just the day before, a friend explained the rules of the format to me over the phone. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do and how to get out of the ordeal without a shameful score. I approached one of the tournament organizers and asked her if she had any advice for a newbie who had never drafted before. she was busy, so she settled for a two-word piece of advice: take creatures. It turned out to be a very good tip since I managed to go 2:1. However, I took this first successful experience too far. Next draft I built a 22 creature deck. It wasn’t so great…

Cost of creatures in mana

As we learned in the second chapter, creatures are relatively sensitive to mana cost, meaning that their effectiveness tends to increase the faster you cast them. Therefore, the cost of a creature in mana greatly affects how we evaluate it, and a difference of just 1 mana in the cost may determine whether it will be considered a good, mediocre or bad creature. In general, it can be said that a creature without attributes will be considered good if its mana cost is half or less than the sum of its power and toughness (Commonly called “The Vanilla Test”:

| Mana Cost | Playable | Good | Excellent |

| 1 | 1/2 | 2/1 | 2/2 |

| 2 | 2/2 | 2/3 3/2 | 3/3 |

| 3 | 2/3 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/3+ |

| 4 | 3/3 | 4/4 | 4/4+ |

| 5 | 4/4 | 5/5 | 5/5+ |

| 6 | 5/5 | 6/6+ | 6/6++ |

| 7 | 7/7 | 7/7+ | 7/7++ |

| 9 | 7/7+ | 7/7++ | 7/7+++ |

Generally, each ability (first strike, vigilance, trample, fear, flash etc.) increases the cost of the creature by half a mana or complicates the mana composition by one (a 2/2 creature costing W1 mana becomes a 2/2 with first strike that costs WW). Good evasion abilities, such as flying or unblockability, increase the mana cost by 1 full mana.

Cost of creatures in cards

The measurement of costs in cards is more complex when applying it to creatures and other permanents in comparison to instances or sorceries. As we learned in Chapter 3, a good spell will be considered one that is able to keep the card balance between me and my opponent: the opponent will have to give up at least one card as a result of my spell. When we evaluate the effectiveness of a creature, we expect that it will force the opponent to waste a card of his own. But how can we know in advance what the creature’s effect will be on the balance of cards? Consider for a moment a 1/1 creature that costs 1 mana. This creature meets the double standard test: its mana cost is half the sum of its power and toughness. Why, then, is this creature considered unplayable (in the absence of additional abilities of course)? Indeed, its mana cost is not problematic but rather the fact that we will almost certainly not be able to exchange it for an opponent’s card (or neutralize an opponent’s creature by the threat of a possible exchange). Usually, this creature will have one of the following two effects: prevent the following X damage (chump blocking) or add +1/+0 to another blocker creature (blocking along with another creature). This is a modest effect for a spell. If the player is lucky enough to play this creature on the first turn of the game, it will be possible to add 1–2 damage to the opponent in addition to the effects described above. This still does not make the card attractive.

Now take a 2/2 creature for 2 mana. No doubt, it isn’t a big deal, but the likelihood that we will be able to exchange it for an opponent’s creature is much greater (the fact that it is sensitive to the opponent’s removals does not change anything. Removals are a card like any other). When it comes to evaluating a particularly big creature (e.g., 6/6), there is a high probability that the opponent will have to sacrifice more than one card to deal with it (for example, two creatures or a creature + combat trick). A big creature, then, tends to give a card advantage, and we pay for this advantage by being able to cast it only late in the game.

Power/toughness ratio:

Creatures with an unbalanced power/toughness ratio (example: 1/6, 6/1) tend to be situational when compared to creatures with balanced power/toughness ratio (for example, 3/4, 4/3). The reason is that the lower stat value becomes a handicap in certain situations, making the card less usable. Take for example a 1/6 creature. The offensive ability of this creature is limited due to its low power value. This makes it situational in terms of the frequency of optimal activation: they are useful in action modes when you want to stabilize the game or gain time. By contrast, when you are applying pressure and want to draw aggressive creatures that will make it difficult for the opponent to stabilize, drawing such a creature will not be useful. This does not mean that defensive creatures, due to their situationality, are bad and do not deserve to see the battlefield. Some decks, for example, are based on a strategy of delaying the early stages of the game and taking over the battlefield in later stages. In such decks, defensive creatures will be more useful because the frequency of their optimal use will be higher than it is in aggressive decks.

Now take as a counter example a 6/1 creature. Imagine a situation in which the opponent has no creatures capable of blocking this creature: the game will be over very quickly. Yet, imagine that the opponent manages to play a 1/1 creature. she completely neutralizes the creature’s aggressiveness (since an attack would lead to an unprofitable exchange). If such a situation develops, there is nothing left for the 6/1 creature but to remain on the defense in the hope of exchanging itself with one of the opponent’s creatures. Also, the fragility of this creature makes it easy prey for the opponent’s removals.

To summarize, an extreme imbalance in the power/toughness ratio makes a creature situational in terms of the frequency of the optimal operation of the card. Does this mean that using such creatures is not recommended? Of course not. This is where the player’s assessment of his deck comes into play. Players should ask themselves how frequently situations arise in which the creature will be effective. This of course depends on the type of strategy they are applying. A deck that aims for a strategy of containment in the early turns of the game in order to develop an advantage in later turns may see creatures with high toughness as a real asset. Conversely, an aggressive deck with many removals and aggressive creatures may find that the fragility of the 6/1 creature is not a liability: the removals allow it to thin out and sometimes even eliminate the opponent’s defense, thus making this creature more effective. Even if the opponent has creatures left to block, she will have to block this creature (due to its damage potential) and thus allow the other creatures to pass through.

Creature abilities and drawbacks

Abilities improve the creature’s efficiency. However, as in real life, there are no free meals in MTG. The creature will almost always have to ‘pay’ for its special abilities by reducing its effectiveness in other respects: high casting cost, certain drawbacks and more. That’s why it’s important to learn to evaluate the effectiveness of the different abilities, or in other words: is the deal profitable for me? One of the ways to determine this is to check the stability of the creature’s abilities. This is done through the frequency and flexibility tests. Since creatures in MTG enjoy countless different abilities, I won’t be able to address them all. I will only discuss the main abilities, assuming that the same analysis method is also suitable for evaluating the stability of all others.

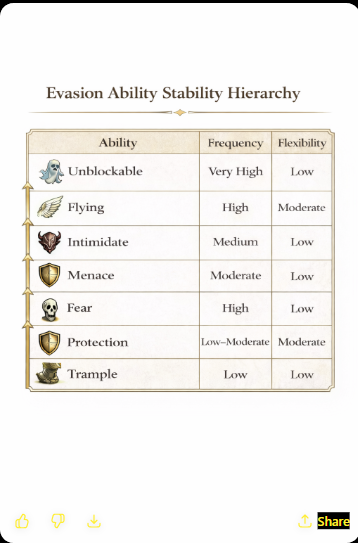

Evasion abilities

Evasion abilities allow an attacking creature to inflict damage directly on the opponent without being blocked. In other words, an evasive creature is a creature that benefits from a feature that reduces or eliminates the opponent’s ability to block it. Therefore, in terms of the action mode axis, this ability will be effective in offensive, race and especially standstill situations. It also follows that the effectiveness of this ability increases as the value of the creature’s power is higher. The effectiveness of an evasion ability is measured by how often it allows a creature to pass through the armies of the opponent’s troops. Since often the creature’s ability to slip through the defenses depends on the formation of certain conditions, it is possible to create a hierarchy of these different abilities according to the frequency of their ultimate activation. Let’s discuss them one by one:

Unblockable:

This is considered the most effective evasion ability because it is always functional. Therefore, this feature is the most stable in terms of the frequency of its activation. Yet, this feature does not enjoy any flexibility: nothing else can be done with it except for attacking.

Flying:

Flying is also considered a good evasion ability due to the relative scarcity of creatures capable of blocking a creature that benefits from this trait. Certain colors (red, green) have limited access to flying creatures, even though green also has a limited number of creatures with reach. Usually, the number of creatures that benefit from this ability or are able to block flying creatures stands at roughly 20%–25% of all creatures in a certain set. This explains why the frequency of activation of this ability is relatively high. Also, unlike unblockability, flying is an ability that also benefits from flexibility: it also contributes to the creature’s defensive ability since creatures with flying can block other creatures with flying.

Intimidate:

The case of intimidate is more problematic to analyze. The effectiveness of this ability depends on the chance that the opponent will not play the color of the attacking creature. In a limited environment, this chance is usually around 60% (the assumption is that the opponent plays two main colors. In MTG there are 10 possible combinations of color pairs, 4 of which include the color of the attacking creature. Therefore, the chance that the opponent will play this color is around 40%, and therefore the ability will be functional 60% of the time). However, even when the opponent plays that color, still only half of his creatures (roughly) will be able to block a creature with intimidate, so this ability will still have some value. Therefore, the frequency of activating this ability can be estimated mediocre at best. On top of that, this feature does not enjoy any flexibility.

Protection from Color:

This ability gives the creature a limited evasion ability, somewhere around 40% (the chance that the opponent plays a creature of the relevant color), but even in this case its evasion requires the existence of an additional condition: the absence of creatures in the opponent’s other main color. That is why this ability is very limited in terms of how often it can be used as an evasion. However, this ability is relatively flexible because it gives the creature other advantages: it is immune to damage of the relevant color and removals of that color cannot target it.

Trample:

This ability is not really an evasion because it doesn’t prevent creatures from blocking the attacking creature. However, it allows the trampler to inflict damage on the opponent that exceeds the sum of the toughness of the creatures blocking it, thus it functions as a sort of evasion feature. What are the most common situations in which this ability will be effective? It depends on the value of the creature’s power. Usually players avoid champ blocking (blocking in which the blocking creature is destroyed without eliminating the attacking creature) because they are loyal to the principle of maintaining card balance. However, against a particularly big creature, this strategy makes sense because it prevents the loss of many creatures in exchange for the elimination of a single attacking creature. It allows the defending player to gain time and is particularly effective in a racing mode. Trample neutralizes this strategy, so it will be more relevant the greater the power of the creature is. Practically, only in a creature with power 4 or higher will this feature enjoy stability in terms of the frequency of its activation.

Stability Analysis of Creature Abilities in MTG

Other abilities

Haste: This ability is only effective when the player is in attack or race mode. This feature is better the higher the value of power of the creature.

First Strike: This ability is only effective when the power of the creature benefiting from it is sufficient to prevent its own elimination. These situations are more common in defense than in attack due to the defender’s ability to choose the blocking creatures. Therefore, first strike will be effective mainly in defense and race modes, where blocking is very relevant. This feature will be better the higher the total power of the creature.

Vigilance: This ability is effective in defense or race modes. It will be better the higher the creature’s toughness value.

Drawbacks

A drawback is a feature that reduces a creature’s effectiveness. Usually this is a ‘payment’ that the creature pays for a particularly good ratio between its cost and stats. There are different types of drawbacks: function liabilities (for example, the creature cannot block), cost liabilities (you are required to sacrifice another creature when it enters the battlefield) and more. A creature’s drawbacks, just like its abilities, are relevant in assessing its stability. Here too, the benchmark is the frequency test. The more common the situation in which the drawback manifests itself, the more situational the creature will be. However, as compensation for its drawbacks, the creature receives other advantages, such as a high value of power/toughness relative to its mana cost. This makes such creatures especially good in situations in which they can be used. Here are some examples of common drawbacks:

Defender: Creatures with this feature cannot attack. This makes them situational in terms of the frequency of their activation state: only in defense or race mode will a creature with this drawback be effective. If the deck is based on a delay strategy, then in terms of the frequency of its activation, this creature will be more stable.

Can’t Block: Creatures with this feature cannot block. This makes them completely ineffective in defensive mode and less effective in race mode.

Must Attack Each Turn If Able: Creatures with this feature must attack. This limitation is similar to the ‘can’t block’ limitation in that it deprives the creature of the ability to block (except for the opponent’s turn after it is cast). However, this feature suffers from an additional drawback in that it requires the creature to attack even when this is not profitable. Therefore, in terms of the frequency of its activation, this feature will be even worse than the previous one.

The flexibility of creatures that benefit from abilities

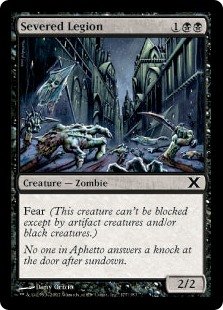

As we have seen, one way to evaluate the effectiveness of a creature with a certain feature (ability or drawback) is by analyzing the frequency of activation of that feature. Yet the stability of the creature is not measured only by this test. It is equally important to analyze the creature’s flexibility, meaning the degree to which it will be effective even when the ability is not optimal. We will define the creature as stable if it is usable even without the ability. By contrast, a creature that loses almost all its value without its ability will be defined as situational. Let’s give an example: Look at two creatures, Severed Legions and Plague Beetle. Both creatures benefit from an ability that gives them evasion if certain conditions are met. If we put their abilities to the frequency test, we will get a fairly clear result: the situations in which the Legions cannot be blocked are more frequent than the situations in which the Beetle cannot be blocked (intimidation is superior to landwalk as an evasion feature). Now, in the absence of the feature, which creature is more effective? A 2/2 creature at 3 mana is very mediocre but still playable. Conversely, a 1/1 creature for 1 mana is good for almost nothing. So, while the Legions are somewhat flexible, the Beetle is not.

Plague Beetle

mana costs:

mana amount: 1

complexity: 1

Severed Legion

mana costs:

mana amount: 3

complexity: 2

Which is better?