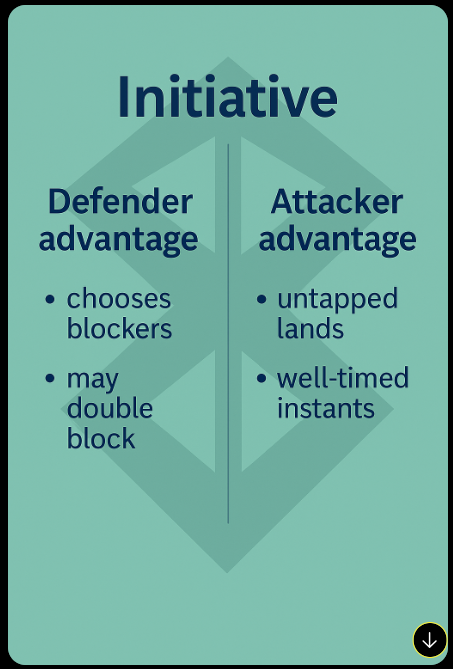

Initiative

In MTG there are two rules that shape the nature of the game in a very dramatic way. The first rule is the one that allows the defender to determine the conditions of engagement in the combat phase: she is the one who can choose which attacker to block with which creature. Moreover, it can block a creature attack by multiple creatures. The attacking player does not enjoy this privilege and is therefore at an inherent disadvantage. The second rule that further enhances the advantage the defender derives from the ability to determine the conditions of the combat phase is the one that cancels all the damage done during the turn: creatures that were not destroyed are completely ‘healed’ on the next turn. As a result, the defender can, by double blocking, eliminate the attacking creature at a reduced cost for herself: a good trade.

The two rules together give the defender a serious advantage and this affects the nature of the game dramatically (for the better, it must be said). Just think for a moment how the game would have looked if the attacking player had been allowed to choose how his creatures would block. In order to overcome the ‘defender’s advantage’ that is built into the game, the attacker can use two tools: use creatures that benefit from evasion abilities, effectively cancelling the defender’s advantage; or use the one advantage available to the attacker in the game: initiative.

There is an important rule in the game that offsets the ‘defender’s advantage’ by giving the initiative to the attacker: only on the attacker’s turn do the lands become operative again (untap) and thus make the mana available. As a result, in many cases the attacker benefits from being free to use mana while the defender is unable to generate mana or is able to generate only part of it. In this situation, the attacker can, by using instances like CT or eliminations, take advantage of this and cause the defender’s ability to block with more than one creature to become a double-edged sword. With a well-timed instant, the attacker can bring eliminate two or more blockers at the cost of one card, thus gaining an advantage in the card balance.

For example: when two creatures block a large creature, eliminating one of them may result in the defender also losing the other without being able to eliminate the attacking creature. As a result, the very act of attacking when the attacking player has free mana while the defender is tap-out presents the defender with a dilemma and thereby gives an advantage to the attacker. To benefit from the initiative advantage, the attacking player must:

*Include in the check a number of removals (instances) and CT that allow her to profit from the advantage provided by initiative.

*Try as far as possible to play her spells only after the combat phase and not before it, thus keeping the full mana open and thereby increasing the defender’s uncertainty.

*Be sure to take advantage of the turns in which the defender cannot produce mana because she has already used it in his turn. A defender with cards in hand and open mana is dangerous because she enjoys both the inherent advantage of the defender and the ability to surprise the attacker with his own CT. Since the first turns of the game are the ones in which the defender has difficulty casting spells and still keeping mana open (due to a disadvantage in mana-producing means), this is the stage in the game at which the attacker can make the most of the advantage that the initiative gives her.

Concentration of efforts

The common way to win in MTG is to reduce the opponent’s life points to 0. It does not matter who placed more creatures on the battlefield or what the card balance is at the moment of victory, as long as the player managed to reduce her opponent’s life to 0, she wins. The player must focus his actions on this goal alone, even if different means may lead to that end. While in constructed it is possible to identify different strategies to achieve this purpose—beatdown, control or combo—in a limited environment the strategies tend to resemble one another. The decks in a limited environment, almost without exception, are rich in creatures.

Attacking the opponent with these creatures is the most common way to win the game. Therefore, the principle of concentration of efforts, or by its other name ‘concentration of power’, can be broken down into a series of principles that are relevant as rules of thumb in this environment:

*The player must use all the tools at his disposal to promote victory. Therefore, as a rule, you should not keep creatures in your hand that may contribute to a victory unless there is a special reason to do otherwise (see the reserve principle). Remember that any creature, even if it is relatively weak, may ultimately be the one that deals the final blow.

*The ability to produce mana must be utilized to the maximum extent in order to maintain the tempo. The order of casting spells should be adjusted so that the amount of unused mana is minimal. This is of course without forgetting additional considerations that may lead to an exception to this rule. Usually, the order of casting the spells must be planned so that the momentum lasts—for example, aggressive creatures before creatures that fulfill non-aggressive functions (this is to the extent, of course, that the initiative is in the player’s hands). Both rules require advance planning. It is important to understand that the order in which the spells are cast at the beginning of the game is of great importance and must be given thought and not performed automatically.

*If we put pressure on the opponent at the beginning of the game and manage to bite off a significant portion of his life points, it is often worth continuing to exert pressure even at the cost of unwanted trades or even one-sided loss of creatures (impairing the card balance). This line of action is mainly desirable when the player’s deck is based on early pressure and its effectiveness decreases as the game develops.

Reserve

The need to maintain a reserve is one of the most important principles of the art of war. The forces left in the reserve allow the commander to take advantage of success on the battlefield by directing the reserve to the weak point discovered in the enemy’s ranks or, conversely, filling a gap discovered in his own ranks and thus saving his army from defeat. Even in MTG it is advisable to leave a reserve—spells in hand that are not played but await a decisive moment in the game. Removals are classic reserve cards.

Bad players cast their removals on the first available target the opponent places on the battlefield. A good player knows that removals are too valuable to be wasted like that. She will use them in the same way that the commander uses his reserve: wait for the right timing that will allow her to gain a quantitative or qualitative advantage. For example, getting rid of a powerful creature that cannot be dealt with in any other way.

Not only removals can be used as a reserve. CT are also distinct reserve cards that are better used only under particularly suitable circumstances. Creatures may also serve this role. Experienced players know that it is not always advisable to cast all the creatures in their hands even if they have the necessary mana at their disposal. In certain situations, it is desirable to leave creature spells in hand, waiting for a particularly suitable moment to cast them despite the fact that this goes against the principle of concentration of effort discussed above. For example, when the player suspects that his opponent has a mass removal spell in her hand.

Or situations in which the player has a particularly high-quality creature and wants to make sure that the opponent ‘spent’ all his removals before putting it in danger. A third example is situations in which the creature benefits from a feature that is not yet relevant and the player wants to hide it from the opponent.

Security

The security principle complements the reserve principle. It requires that a player secure his actions so that even if she is surprised by an opponent’s move, she will still be able to minimize the damage. For example, a player must sometimes be careful of over-commitment in an attack: a situation in which she attacks with all or most of her creatures and thus abandons defense completely (in some situations it is advisable to do so, but as a rule it is best to avoid this). It is wiser to leave a few creatures to block the opponent’s counterattack, even if under the current conditions such an attack is improbable or not fatal.

A second example of the security principle is the careful use of creature abilities that are limited in the number of times they can be used in a turn (due to the need for tap, mana cost or other limitations). For example, we often want to avoid using the ability of a creature that can pump another creature (add to it power/toughness) (for example, to cause greater damage to the opponent) to allow the use of this ability in emergency situations (for example, to protect a creature from an opponent’s removal).

This is an example of the tension that sometimes exists between the principle of security and the principle of concentration of efforts. The security principle also requires that we free mana in order to allow the use of CT in our hand or our creatures’ abilities on the battlefield. In general, we will strive to wait until the end of the opponent’s turn in order to cast instants or use different abilities because by doing so we minimize the opponent’s ability to surprise us.